Is Google Books Leading Researchers Astray?

A new paper argues that the service isn’t as useful as it seems.

Jacob Brogan | October 13, 2015

|

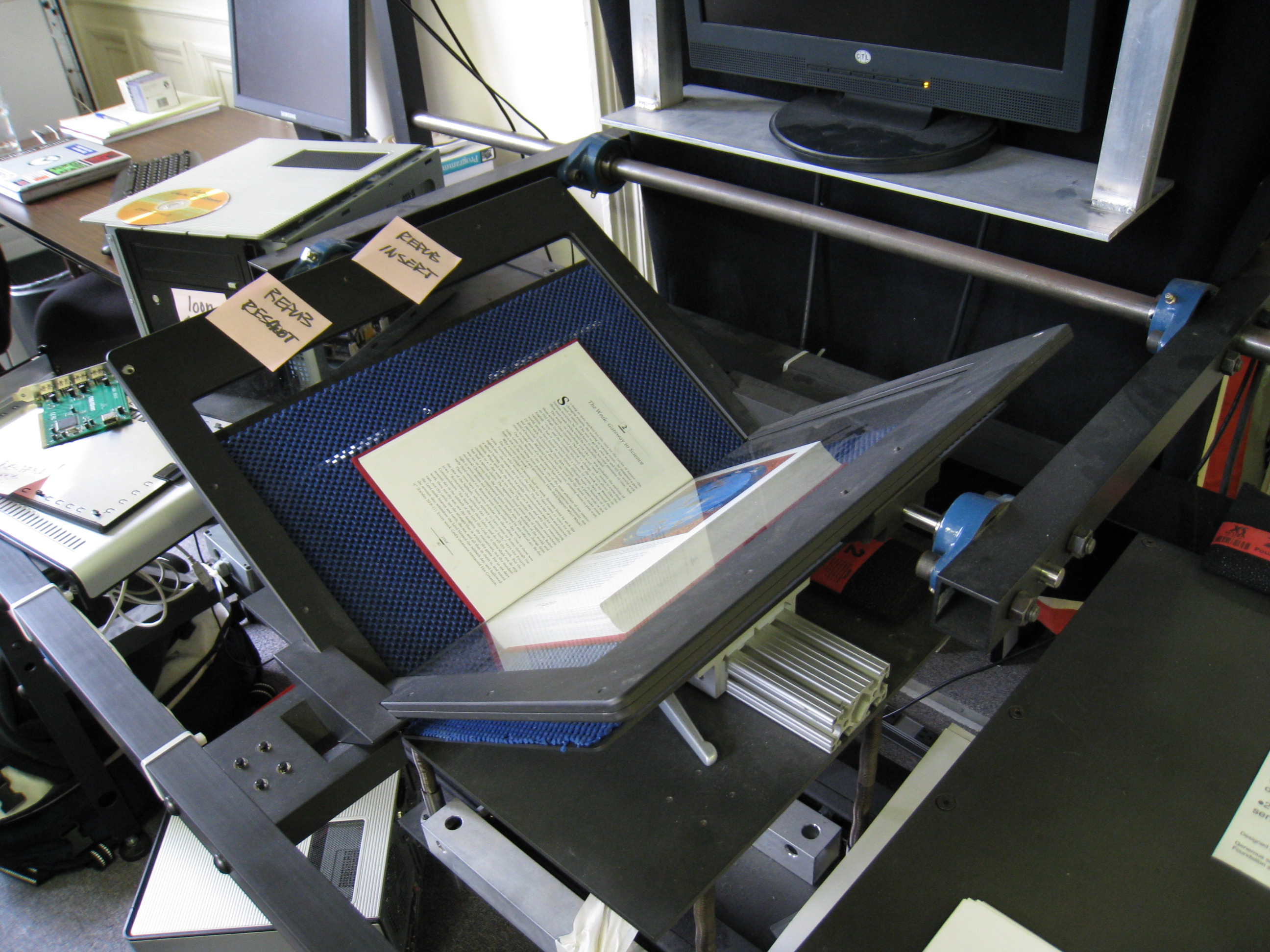

| Internet Archive book scanner. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_scanning |

<more at http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2015/10/research_suggests_google_books_isn_t_as_helpful_as_some_believed.html; related links: http://arxiv.org/abs/1501.00960 (Characterizing the Google Books corpus: Strong limits to inferences of socio-cultural and linguistic evolution. Eitan Adam Pechenick, Christopher M. Danforth, and Peter Sheridan Dodds. arXiv:1501.00960v2 [physics.soc-ph]. [Summary: It is tempting to treat frequency trends from the Google Books data sets as indicators of the "true" popularity of various words and phrases. Doing so allows us to draw quantitatively strong conclusions about the evolution of cultural perception of a given topic, such as time or gender. However, the Google Books corpus suffers from a number of limitations which make it an obscure mask of cultural popularity. A primary issue is that the corpus is in effect a library, containing one of each book. A single, prolific author is thereby able to noticeably insert new phrases into the Google Books lexicon, whether the author is widely read or not. With this understood, the Google Books corpus remains an important data set to be considered more lexicon-like than text-like. Here, we show that a distinct problematic feature arises from the inclusion of scientific texts, which have become an increasingly substantive portion of the corpus throughout the 1900s. The result is a surge of phrases typical to academic articles but less common in general, such as references to time in the form of citations. We highlight these dynamics by examining and comparing major contributions to the statistical divergence of English data sets between decades in the period 1800--2000. We find that only the English Fiction data set from the second version of the corpus is not heavily affected by professional texts, in clear contrast to the first version of the fiction data set and both unfiltered English data sets. Our findings emphasize the need to fully characterize the dynamics of the Google Books corpus before using these data sets to draw broad conclusions about cultural and linguistic evolution.] and http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/techtank/posts/2015/07/01-google-book-digitization (Extended Collective Licensing: A way forward on book digitization? July 1, 2015)>

No comments:

Post a Comment